A visit to Bletchley Park, an early home of computing

Bletchley Park, England

In the bland concrete buildings shown below, on the grounds of an English country mansion, a part of World War II was won, and a part of computing was born. This is Bletchley Park, the place where the German codes were broken. I went for a visit with the family.

In the bland concrete buildings shown below, on the grounds of an English country mansion, a part of World War II was won, and a part of computing was born. This is Bletchley Park, the place where the German codes were broken. I went for a visit with the family.

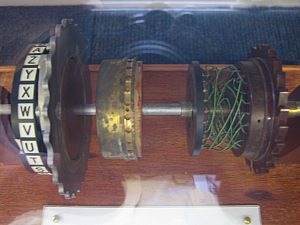

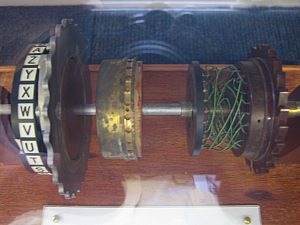

The device on the left is an Enigma machine, the most famous German encryption machine. Enigma machines are actually a class of device; they're not all alike. They work on a fairly simple principle. A set of rotors, visible at the upper left, convert an input keystroke into an output letter. When you press a key, one of the letters above the keyboard lights up. The rotors advance in position, and if you press the same key again, a different letter will light up. The key to the code produced is in the original position of the rotors. This is a four-rotor machine, which, at 26 positions per rotor, has 456,976 possible keys. To add even more, a series of plugs and wires (visible at the bottom) can be inserted to further mix up the letters.

The device on the left is an Enigma machine, the most famous German encryption machine. Enigma machines are actually a class of device; they're not all alike. They work on a fairly simple principle. A set of rotors, visible at the upper left, convert an input keystroke into an output letter. When you press a key, one of the letters above the keyboard lights up. The rotors advance in position, and if you press the same key again, a different letter will light up. The key to the code produced is in the original position of the rotors. This is a four-rotor machine, which, at 26 positions per rotor, has 456,976 possible keys. To add even more, a series of plugs and wires (visible at the bottom) can be inserted to further mix up the letters.

Here's what an Enigma rotor looks like on the inside, disassembled:

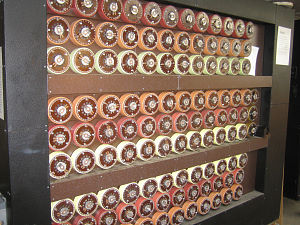

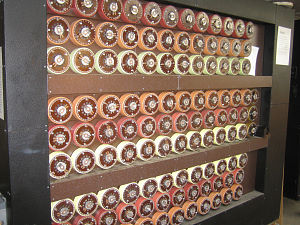

And below is the machine, or rather a mockup of the real one, that broke the Enigma code, saved countless lives, and shortened the war by as much as two years. For some obscure reason it was named after the Italian word for an ice cream sundae, "Bombe," and for one of its inventors, the British mathematician Alan Turing. This is the Turing Bombe. Given an encrypted message intercepted by a listening post and a possible phrase that might be in the message (such as "Heil Hitler," which appeared often in German messages), it searched by brute force for possible rotor combinations of the Enigma machine that would turn the encrypted message into the original one. In effect, it consisted of 36 automated Enigma machines, all running backwards. It wasn't a computer in the modern sense, but an electromechanical search engine.

In the bland concrete buildings shown below, on the grounds of an English country mansion, a part of World War II was won, and a part of computing was born. This is Bletchley Park, the place where the German codes were broken. I went for a visit with the family.

In the bland concrete buildings shown below, on the grounds of an English country mansion, a part of World War II was won, and a part of computing was born. This is Bletchley Park, the place where the German codes were broken. I went for a visit with the family. The device on the left is an Enigma machine, the most famous German encryption machine. Enigma machines are actually a class of device; they're not all alike. They work on a fairly simple principle. A set of rotors, visible at the upper left, convert an input keystroke into an output letter. When you press a key, one of the letters above the keyboard lights up. The rotors advance in position, and if you press the same key again, a different letter will light up. The key to the code produced is in the original position of the rotors. This is a four-rotor machine, which, at 26 positions per rotor, has 456,976 possible keys. To add even more, a series of plugs and wires (visible at the bottom) can be inserted to further mix up the letters.

The device on the left is an Enigma machine, the most famous German encryption machine. Enigma machines are actually a class of device; they're not all alike. They work on a fairly simple principle. A set of rotors, visible at the upper left, convert an input keystroke into an output letter. When you press a key, one of the letters above the keyboard lights up. The rotors advance in position, and if you press the same key again, a different letter will light up. The key to the code produced is in the original position of the rotors. This is a four-rotor machine, which, at 26 positions per rotor, has 456,976 possible keys. To add even more, a series of plugs and wires (visible at the bottom) can be inserted to further mix up the letters.Here's what an Enigma rotor looks like on the inside, disassembled:

And below is the machine, or rather a mockup of the real one, that broke the Enigma code, saved countless lives, and shortened the war by as much as two years. For some obscure reason it was named after the Italian word for an ice cream sundae, "Bombe," and for one of its inventors, the British mathematician Alan Turing. This is the Turing Bombe. Given an encrypted message intercepted by a listening post and a possible phrase that might be in the message (such as "Heil Hitler," which appeared often in German messages), it searched by brute force for possible rotor combinations of the Enigma machine that would turn the encrypted message into the original one. In effect, it consisted of 36 automated Enigma machines, all running backwards. It wasn't a computer in the modern sense, but an electromechanical search engine.

<< Home